Last week was National Pollinator Week! The week is organized by Pollinator Partnership to raise awareness about native pollinators.

This post talks about native pollinators, the challenges they face, and ways we can help. I hope it inspires you to make a small change to benefit these important species.

Why Are Pollinators so Important?

Pollinators are responsible for the reproductive success of 87% of flowering species!1 Flowering plants, also known as angiosperms, are the largest and most diverse group within the plant kingdom.9 To put that into context, “more than 250,000 species of flowering plants have been described” and an equal number are likely waiting to be discovered.7

All these plants provide important nutrients and resources to other organisms.7 Flowering plants are “at the base of most terrestrial and aquatic food webs.”7 Humans rely directly and indirectly on angiosperms for “food, fiber, drugs, and fuel.“7 According to the US Department of Agriculture, “about one-third of the human diet comes from insect-pollinated plants!”2 We can thank pollinators for chocolate, strawberries, nuts, and many of the foods we’ve come to love.

It’s difficult to quantify the services pollinators provide, but “values are likely $4-5.5 billion/year for Canadian crops” and that’s only counting the work of managed honeybees – not our native pollinators.3

Flowering plants are also an important part of human aesthetic, recreational, and cultural pursuits.7 Floral bouquets feature prominently at weddings, gardening is a favourite pastime, and many cultures hold specific plants as sacred. What’s more, we’re still learning about the therapeutic benefits of plants and nature.

What Exactly is Pollination?

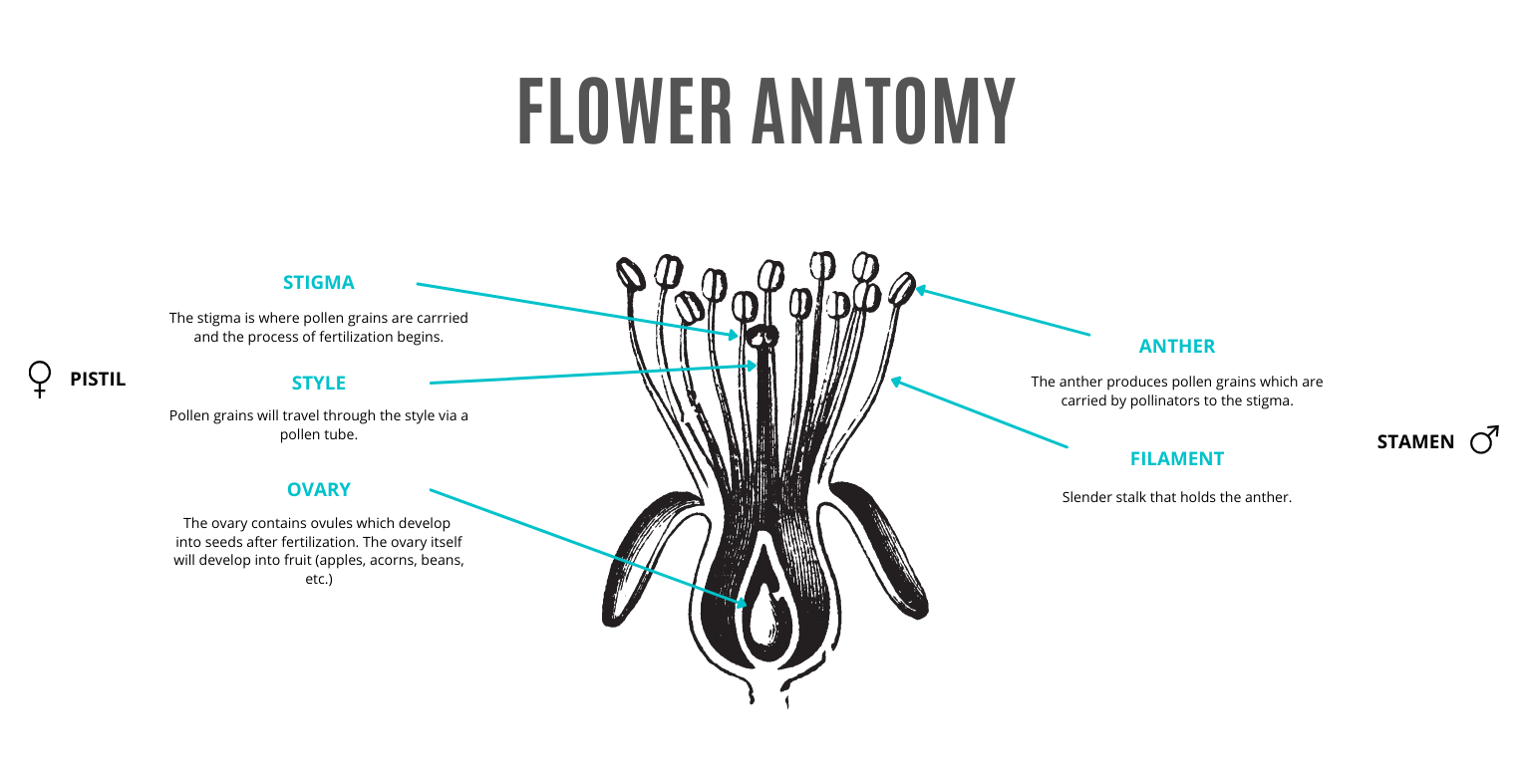

Pollination is the passing of pollen from male to female reproductive parts of a flower (from anther to stigma) which results in fertilization. While some plants are able to self-pollinate, the majority of flowering plants “depend on the transfer of pollen from other individuals (cross-pollination).”7 This is where pollinators come in handy!

In search of food (nectar and pollen), pollinators fly from one flower to another inevitably spreading pollen from flower to flower. The relationships between pollinators and flowering plants is considered mutualistic.10 This means that both species benefit from the interaction. Flowers depend on pollinators for fertilization and pollinators get a nutritious meal out of the deal.

Who Are Our Pollinators?

You’ve probably heard that bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds are important pollinators. But, did you know that bats, moths, flies, beetles, wasps, and ants also play a critical role in pollination?

Flowering plants come in all sorts of shapes, sizes, and colours. Not all pollinators are suited to all flowers. In fact, different pollinator species “co-evolved physical characteristics that make them more likely to interact successfully.”10 Generally speaking, birds are attracted to large funnel like flowers with strong perch supports, whereas bees are better able to access shallow tubular flowers with landing platforms.10 Both bats and beetles like bowl shaped flowers, with bats targeting flowers that open at night.10

Bees

Most scientists agree that “bees are the predominant pollinators for most plants and ecosystems.”1 In Canada, there are at least 855 known species of bees with over 100 currently undescribed species.3 The common eastern bumble bee (Bombus impatiens) is one of the largest native bumble bees in eastern Canada and is considered one of the most important pollinator species in North America.12

Flies

After bees, “flies are the second most frequent visitors to flowers overall.”1 Pollinator flies “are concentrated in only three families: Syrphidae (hoverflies or flower flies), Bombyliidae (bee flies), and Tachinidae (tachinid flies). Of these three groups, the syrphid flies are likely the most important flower visitors.”1 Scientists recently discovered new flower fly species in the Maritimes that were previously known to exist only in the provinces of Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba.13 New discoveries like these show that we still have much to learn about our native pollinators.

Butterflies and Moths

While not doing nearly as much pollination as bees and flies, butterflies and moths still play an important role. Uniquely, they have been shown to carry pollen farther than other insects. Scientists think this “long-distance pollen transfer could have important genetic consequences for plants,” possibly leading to increased fitness.1

Bats and Birds

Birds and bat are also important pollinators. Hummingbirds, found only in North and South America, are the most abundant of vertebrae pollinators.1 These birds feed by hovering and sticking their long tongues into flowers to draw out nectar. During feeding they inadvertently collect pollen on their feathers spreading it to the next flower they visit.14

As for bats, there are two families that have flower-visiting species: the leaf-nosed bats (Phyllostomida) and the fruit bats (Pteropidae)1. Canada is not home to any pollinator bats, though they play an important role in other parts of the world. If you’ve ever enjoyed a drink of tequila, you can thank the long-nosed bat who pollinates blue agave plants.

What Are Threats to Pollinators?

Many scientists have raised concerns about the decline of pollinators globally.1 While these threats are still being understood, research suggests that they include: pesticides, habitat loss, pathogens from introduced species, competition with non-native and managed species, and climate change.3

As humans dominate more and more of the land, interactions between plants and pollinators is changing.1 Urbanization and agriculture has replaced forests and meadows that pollinators have come to rely on. These transformed ecosystems, whether agricultural or suburban lawns, are often subject to multiple applications of pesticides which can cause metabolic, immune, and reproductive dysfunction in pollinators and other species.18 Furthermore, non-lethal doses of pesticides have also been found to negatively affect the foraging behaviour of bees.19

Human driven climate change is also transforming ecosystems. One concerning impact of climate change is the disruption of seasonal timing of flowering plants and pollinator emergence.5 When plant flowering does not line up with pollinator emergence, the reproductive success of the plants that pollinators rely on is at risk. It’s a lose-lose situation.

To make matters worse, one major obstacle to understanding and protecting pollinators is that the conservation status of many species are unknown – there just isn’t enough research. In Canada, we know eight species of bees are at-risk of extinction: three are considered endangered, two are threatened, and three are of special concern.3

Bee-Washing: The Problem with Non-Native Species

One of the least understood issues facing pollinators is the threat of non-native species like the European honeybee (Apis mellifera).3 Apis mellifera can out compete native bee species for floral resources and it has been found to spread pathogens to native species.7

This is bad news for our native pollinators and the plants that depend on them. Native bees often have adaptions to local flora. In the Maritime provinces, native bumble bees, andreid bees, and halictit bees were found to be more effective pollinators of native low-bush blueberries than introduced species.11 Native bumble bees visited more flowers per minute and had greater success of pollination than introduced honey bees.11 They were also “able to carry greater pollen loads and deposit more pollen grains per minute than other bees recorded.”11

In Canada, pollinator conservation efforts have focused on non-native species to the detriment of native species. While it is true that some beekeepers have noticed colony collapse in their honey bees, these bees are not endangered.4 Nonetheless, many companies and organizations purporting to #savethebees focus only on managed honey bee populations.4 This focus has distorted public perception of the problem to the detriment of native species.3

This deception has become so widespread that researchers at York University coined the term ‘bee-washing’ to describe “a type of greenwashing where companies mislead consumers to buy products or subscribe to services under the pretense of helping bees.”4 Bee-washing improves the public image of companies, while driving the decline of native bee species.4

What Can We Do to Help?

It’s clear that we need large societal changes that combat habitat destruction, climate change, and unsustainable practices to protect our native pollinators. But, there are also things we can do as individuals to help pollinators and, rest assured, people want to help!

A nation-wide survey shows that Canadians have strong support for conservation efforts, including protection of our pollinators, but “nearly one-quarter (23.9%) did not know how they could personally help.”3 So, let’s dive into ways we can make a difference!

1. Rethink Your Lawn

Weed free lawns have little nutritional or habitat value for our pollinators.6 Consider trading in your manicured lawn for a more naturalized one. Some people are even turning their lawns into lovely wildflower meadows. If you’re worried about what the neighbours will think, try talking to them about what you are doing and why it’s beneficial. Who knows, maybe you’ll win them over! That said, don’t be surprised if you do face opposition. Some municipalities have rules against “unkempt” lawns, but people are pushing back and winning.

A simple thing you can do to help pollinators is wait until late spring to mow your grass. This allows pollinators to access some early blooming plants. Couple this with mowing less generally and your yard will become an occasional retreat for pollinators.

2. Plant Native Flowers

If the idea of an unkempt lawn is too much for you, you can always plant some native flower species around your property. Even small flower gardens can provide benefits to pollinator communities. If you live in an apartment building with a balcony, you might be surprised by how many pollinators visit a container garden.

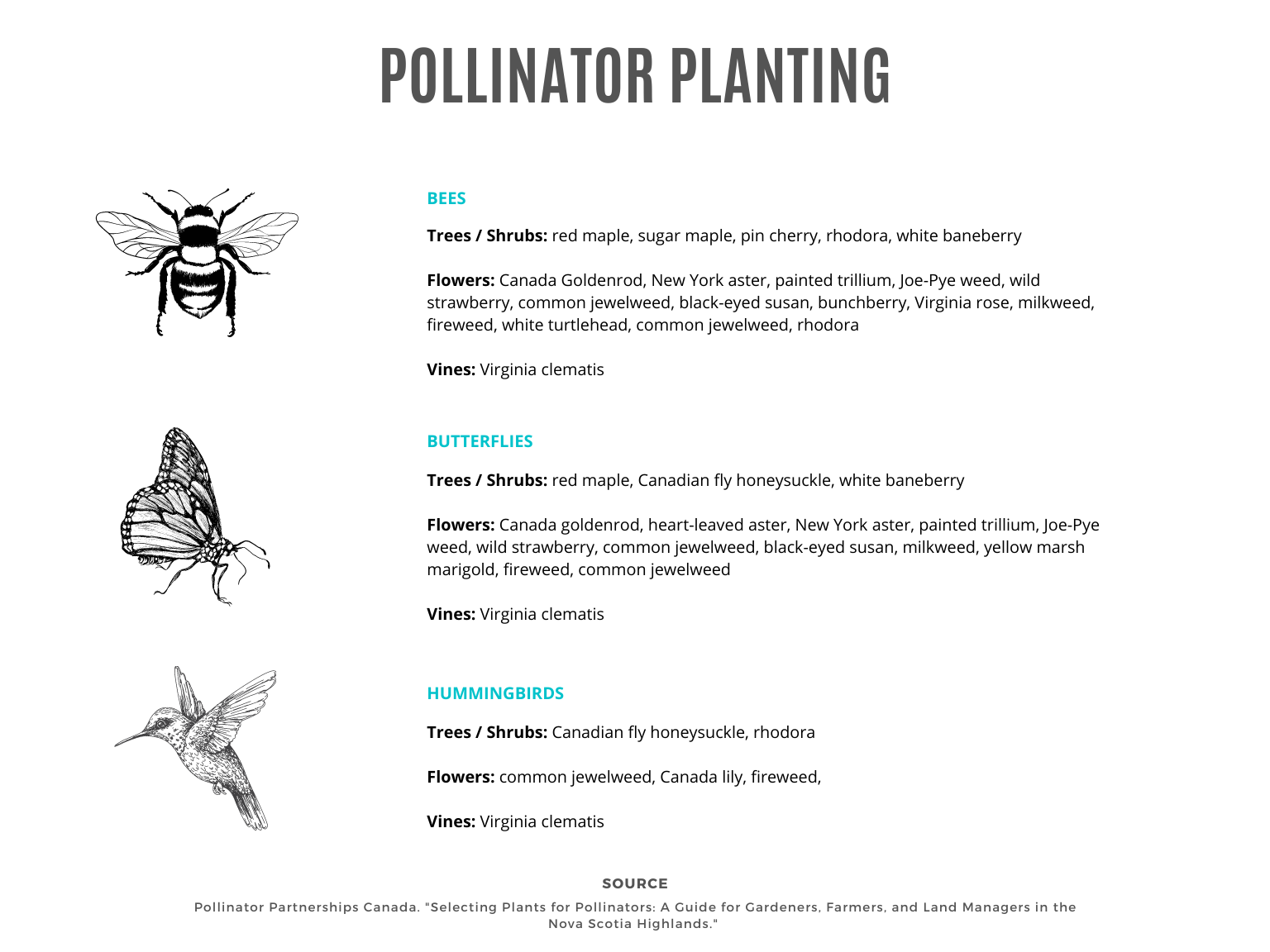

Try planting flowers of different shapes, sizes, and bloom times. Check out Pollinator Partnership Canada’s Ecoreginal Planting Guides for help finding beneficial native species.

3. Avoid Pesticides

Avoid using pesticides in your lawn and garden. If you are having issues with pests, try companion planting as a way to attract beneficial insects and deter those that are harmful. Sometimes, it’s best to count your loses and allow nature to take its course. Over time, you’ll find the right plants and plant combinations to grow a fruitful garden.

4. Host a Pollinator Planting Day

What if you have no space of your own for growing native plants? Pollinator Partnerships of Canada recommends you host a pollinator planting day at your school, office, local library, or local faith organization. If you don’t know where to start, try contacting a local conservation group. Conservation groups can tell you what local plants would be beneficial and they might be able to send an organizer to help you with your initiative!

5. Create Habitat for Pollinators

Pollinators also need sites for nesting and roosting, and habitat that can protect them from severe weather and predators.15 You can provide this type of refuge by incorporating “different canopy layers in the landscape by planting trees, shrubs, and different-sized perennial plans;” leaving “dead snags for nesting sites;” and grouping “plantings so that pollinators can move safely through the landscape protected from predators.”15

Looking for an excuse to avoid fall yard cleanup? Fallen leaves and debris are important habitat for pollinators to overwinter in – just don’t clean them up too early in the spring.

You can also build or buy insect hotels to attract pollinators. But, keep in mind that many on the market are not ideal homes for insects. Unfortunately, badly designed artificial nesting sites can cause problems that lead to mortality.16 Marc Carlton has a great guide to building, maintaining and overwintering insect hotels.

6. Reduce Mulch

While mulch is helpful to gardeners, it is not ideal for pollinators like ground-nesting bees.8 The David Suzuki Foundation recommends leaving the ground bare or lightly mulched in sunny well-drained areas or placing a few logs in your garden to provide natural nesting sites for bees and other insects.8

7. Turn Off the Lights

With the flick of a switch you can help nocturnal pollinators out! Artificial nighttime lighting can cause confusion and impede “navigation, reproduction, and the ability to find food” for many insects and birds.17 So, turn off your outdoor lights when they aren’t in use.

8. Cut Out Gas Guzzling Lawn Care

If it’s feasible, trade your gas guzzling leaf blowers, lawnmowers, and weed-whackers for electric or manual powered versions. The noise of these machines can impair bird communication and they release air pollutants that harm the respiratory health of all living things.17

9. Stay on the Trail and Leave Fragile Plants in Place

When hiking, careful not to trample on vegetation. Some flowers, like trilliums and lady slippers, take a long time to recover from disturbance and may not come back at all.

10. Keep Track of Pollinator Sightings Using iNaturalist

Parks Canada recommends turning your passion for pollinators into community science through the use of iNaturalist. You can download iNaturalist on your phone and track the plants and pollinators you encounter. If you aren’t sure what you are looking at, the app and its users can help you out! Plus, “every observation you make using iNaturalist becomes part of an amazing database used by scientists around the world to study biodiversity, species distribution, climate change, and more.”8

11. Learn, Educate, Advocate

Get to know some of your local pollinators and plants. You could visit a local botanical garden, attend a guided nature walk, or pick up a reference book from your library. Share what you learn with your kids, family members, and friends.

Try to identify issues in your community that impact pollinators and take action. This could look like: opposing pesticide use in your area, supporting efforts to green your community, encouraging naturalized lawns in your municipality, gathering petition signatures to protect local habitat, or volunteering with a local conservation group.

What Small Change Will You Make?

I hope this post has inspired you to make one or two small changes to create a healthier future for native pollinators. I’d love to hear your ideas or what you plan to do in the comments section!

Other Posts You May Enjoy

From Grass to Garden: Creating Habitat and Biodiversity with Native Plant Gardens

Monarchs: Resilience in the Face of Fragility and Adversity

Acadian Forest: History, Species, and Biodiversity

Sources

Note: Citations correspond with superscript number in the text.

1 Winfree, Bartomeus, and Cariveau. 2011. “Native Pollinators in Anthropogenic Habitats.” Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics.

2 Wenning. 2009. “The Status of Pollinators.” Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management.

3 Vierssen Trip, MacPhail, Colla, and Olivastri. 2020. “Examining the Public’s Awareness of Bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidae: Anthoophila) Conservation in Canada.” Conservation Science and Practice.

4 Charlotte de Keyze. Bee-Washing.com

5 Marshman, Blay-Palmer, and Landman. 2019. “Anthropocene Crisis: Climate Change, Pollinators, and Food Security.” Environments.

6 Marshman. 2022. “Bee Cities and More-Than-Human Communities: Protecting Pollinators in the Anthropocene.” Dissertation – Wilfred Laurier University.

7 Committee on the Status of Pollinators in North America, National Research Council. 2007. “Status of Pollinators in North America.”

8 Parks Canada. 2022. “Adopt Pollinator Friendly Practices.”

9 Britannica. “Angiosperm.”

10 United States Department of Agriculture. “Pollinator Syndromes.”

11 Government of New Brunswick. “Native Bees that Pollinate Wild Blueberries.”

12 Sachman-Ruiz, Narváez-Padilla, and Reynaud. 2015. “Commercial Bombus impatiens as reservoirs of emerging infectious diseases in central México.” Biological Invasions.

13 Weldon. 2015. “7 New Insect Species Found in the Maritimes.” CBC.

14 Winter. “Ruby-throated Hummingbird.” United States Department of Agriculture.

15 Pollinator Partnerships Canada. “Selecting Plants for Pollinators: A Guide for Gardeners, Farmers, and Land Managers in the Nova Scotia Highlands.”

16 Jo-Lynn. 2017. “Insect Hotels: A Refuge or A Fad?” The Entomologist Lounge.

17 David Suzuki Foundation. “How to Attract Pollinators.”

18 Hanif Hashimi, Rahmatullah Hashimi, and Ryan. 2020. “Toxic Effects of Pesticides on Humans, Plants, Animals, Pollinators, and Beneficial Organisms.” Asian Plant Research.

19 Gill and Raine. 2014. “Chronic Impairment of Bumblebee Natural Foraging Behaviour Induced by Sub-lethal Pesticide Exposure.” Functional Ecology.

Thank you for the excellent information!

Thanks for reading and leaving a comment 🙂

These figures are amazing? Did you create them or where did you find them?

Hi Grace, thanks. I created them using Canva. They have stock images for free or with paid subscription.