For most of my life, I couldn’t tell the difference between a pine or spruce, let alone a balsam fir or hemlock. The world outside was a “wall of green.” While I loved being out in the forest, I knew little about it. Today, learning about plants makes me feel more connected to nature and my community.

Maybe you’ve landed here for the same reason, or you’re trying to identify a tree growing in your neighbourhood. Whatever your purpose, this post is an introduction to the coniferous trees in the Wabanaki/Acadian forest. You’ll find some tips for identifying conifers and some information about their historical and ecological importance. Let’s get started!

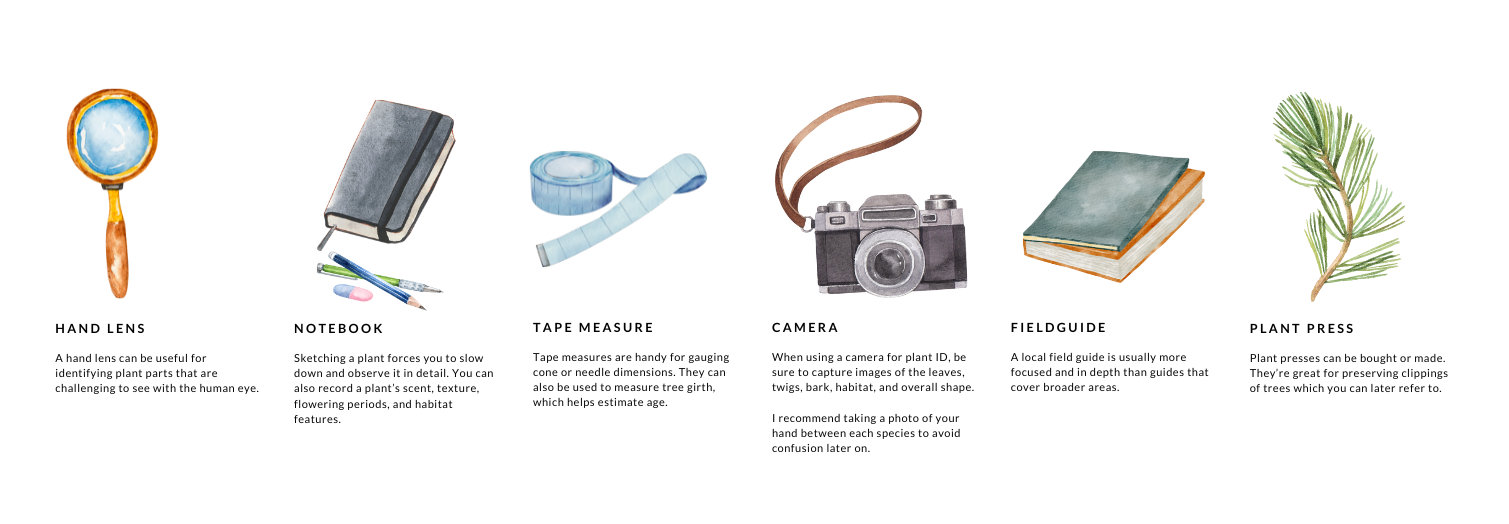

Helpful Equipment

When identifying conifers, you’ll be looking at their leaves, bark, twigs, branching pattern, habitat, touch, and smell. Sometimes, trees share several characteristics making identification tricky. When possible, it’s best to identify plants in the field. Here are some things that will make that easier:

Field Guide

A local field guide is an invaluable tool. Guides covering large areas (i.e. North America) can be overwhelming and there’s more chance for confusion. By choosing a local guide, you can focus on a few trees and later expand your knowledge.

Hand Lens

A hand lens is a small handheld magnification tool. It helps you see small plant parts, like leaf venation, hairs, or the texture of plant surfaces. It’s very useful for identifying conifers that look similar upon first glance (i.e. black and red spruce).

Ruler

Field guides describe leaf and cone sizes. Oftentimes, they’ll have a ruler printed on the back cover. If not, carrying one with you might prove useful.

Camera

When photographing plants for later identification or reference make sure to include photos of the leaves (top and bottom), bark, twigs, habitat, and overall shape. I take a picture of my hand in between each new species, so I don’t confuse them.

Notebook

Some things, like smell and touch, can’t be photographed. Use a notebook to jot down your observations. Sketching a plant also encourages you to slow down and carefully observe it.

iNaturalist

iNaturalist is a great resource for people looking for help with identification. You can see other species recordings in your area, upload your own, and discuss your findings.

ID Basics

If you’re new to identifying conifers, here are some terms that may be helpful:

Needle vs Scale-like Leaves

Conifers have needle-like or scale-like leaves. Needles are straight, thin, and arranged in bunches or individually on the stem. Scales are small, flat, and overlap like shingles.

Opposite vs Alternate Leaves

In botany, leaf arrangement describes how leaves are positioned on a stem. There are three main types: alternate, opposite, and whorled. Alternate leaves are staggered along the stem, with each leaf positioned at a different height, alternating from side to side. Opposite leaves grow directly across from each other on the stem, with two leaves emerging at the same point but on opposite sides. Whorled leaves are arranged in circles, with three or more leaves arising from the same point on the stem.

Bark Features

Trees can be identified by their unique bark patterns, textures, and colours. There are six common types:

Smooth bark: Some trees, especially young ones, have smooth bark with no cracks, scales, furrows or ridges. A young tree with smooth bark may develop fissures or cracks as it ages.

Peeling: Peeling bark comes off in curly strips.

Visible lenticels: Lenticels are small pores in tree bark that help with gas exchange. All trees have them, but they are often more visible on smooth bark.

Cracks in otherwise smooth: Cracks in its otherwise smooth bark resemble stretch marks. Cracks can expose inner bark layers that may have a different colour or texture than the outer bark.

Scales, plates, vertical strips: Scaly bark is made up of small and overlapping scales. Plated bark consists of large and flat plates that can vary in size and thickness. Vertical strips are long, narrow, and run vertically. Scales, plates, and vertical strips all appear loosely attached, as if you could peel them off.

Furrows or ridges: Furrowed or ridged bark has deep grooves or cracks. Unlike scales, plates, and vertical strips, furrowed and ridged bark looks rigid and fixed.

I learned everything I know about bark from Michael Wojtech’s Bark: A Field Guide to Trees of the Northeast. It’s a comprehensive guide to identifying trees by their bark, explaining why different barks grow as they do and how it relates to a tree’s life cycle. The book focuses on the Northeastern United States, but includes many trees from the Wabanaki/Acadian forest. I highly recommend it!

Stomatal Bloom

Stomata are tiny pores on plant leaves that let gases like oxygen and carbon dioxide pass between the plant and the air. Some conifers have a waxy coating called stomatal bloom on their leaves, making white bands on the underside of their needles or in between their scales. This bloom helps waterproof the needles, keeping them dry in rain and holding onto water in dry weather.11 It’s also a helpful way to tell conifers apart.

Wabanaki/Acadian Trees

Now that we’ve covered useful gear and terms, let’s dive into identifying conifers of the Wabanaki/Acadian forest. Altogether, there are ten native coniferous trees in this region: white pine, red pine, jack pine, white spruce, red spruce, black spruce, hemlock, eastern white cedar, tamarack, and balsam fir.

Pines

Pines of the Wabanaki/Acadian forest are tall and beautiful. One quick way to distinguish them from other conifers is by observing their needles which grow in clusters of 2-5. Tamarack is the only other conifer in the area with needles in bundles, but it has bundles of 12-30.

Historically, pines were prized for shipbuilding because of their tall and straight growth. This made them perfect for ship masts and bowsprits.1 Sadly, demand for pines led to widespread harvesting. Today,it is rare to find pines over 200 years old in Atlantic Canada.

White Pine (Pinus strobus)

White pine is the tallest tree in the Wabanaki/Acadian forest. Eagles love to nest at its top to get a wide view of the land.2 Black bears also love white pines. Mature trees have deeply furrowed and strong bark, making them easy for cubs to climb and take shelter in their strong and shaded branches.3 Also, older white pines are often hollow and large enough to serve as bear dens.3

The Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik, and Passamaquoddy peoples boil eastern white pine needles to make a tea rich in vitamin C.4

Needles: Soft, flexible needles grouped in bundles of 5. Each needle is around 2-5 inches long and bluish-green. Needles are round and can be rolled between fingers.

Cones: Large slender cones, around 3-8 inches long, often covered in sap.

Branches: Branches are stacked in whorls.

Bark: Smooth, greyish-green bark when young. As it ages, the bark turns a darker grey and develops large furrows.

Appearance: Tends to have a straight trunk. Overall pyramidal shape, but top foliage can flatten out or appear lopsided from wind damage. 80-110 feet tall.

Habitat: Prefers full sun, sandy, and well-drained soils.

Red Pine (Pinus resinosa)

You can find plantations of red pine in both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. It was used in reforestation efforts after the spread of spruce budworm in the 1970s.

Black bears use red pines as marking posts, scratching and biting the bark to leave their scent. This helps them communicate territory boundaries, presence, and possibly other information to nearby bears.

Needles: Needles are grouped in bundles of two, measuring around 4-6 inches long. Dark green, stiff, and break with a snap when bent.

Cones: Small cones, typically 1.5-2.5 inches long, egg shaped or round.

Bark: Bark is flaky and reddish/pink or brown. It becomes darker and develops a scaly texture as the tree ages.

Appearance: Typically has a straight trunk with a oval or rounded crown. Lower branches droop slightly while upper branches curve skywards. 50-80 feet tall.

Habitat: Shade intolerant, sandy soils, and rocky sites.

Jack Pine (Pinus banksiana)

Jack pine cones are serotinous, meaning they open and release their seeds only when exposed to heat. For this reason, Jack pine is considered a pioneer species in fire succession. It is one of the first trees to establish and grow in post-fire landscapes, helping to stabilize the soil and create conditions for other plant species to colonize the area. Over time, as the forest matures and other tree species establish, Jack pine may become less dominant in the ecosystem.

Needles: Short needles, 1.5-2.5 inches long, grouped in bundles of two and forming a v-shape. The needles are yellow-green and twisted together at the base. They are flat and cannot be rolled easily between your fingers.

Cones: Small and curved cones that are 1-2 inches long. Cones stay shut until exposed to high heat.

Bark: Young bark is reddish-grey to brown. Bark becomes darker and greyer with age. Mature bark appears plated.

Appearance: Trunk is often irregular or twisted with an open and scraggly crown. 40 – 60 feet tall.

Habitat: Acidic soils, sandy, rocky, and well-drained sites.

Spruces

There’s a saying, “never shake hands with a spruce.” Spruces have short, stiff, and sharp needles. There are three spruce species in the Wabanaki/Acadian forest: red spruce, white spruce, and black spruce. Red and black spruce can be really tricky to tell apart. Their bark, needles, and twigs look similar. To make things even more confusing, “red and black spruce naturally hybridize to create intermediate forms.”4

Red Spruce (Picea rubens)

Red spruce is the provincial tree of Nova Scotia. It can survive in “virtually any terrain and condition, and was chosen to represent the strength and resilience of Nova Scotians.”5 Sadly, some climate projections predict that red spruce will decline in the Wabanaki/Acadian forest as the climate warms.6

Needles: Needles are a half inch long. Yellow-green with two faint lines of stomatal bloom on the underside. They’re round and easily rolled between your fingers. There is a brownish-yellow-orange stain at the base of the needle, which appears more red in winter.

Cones: Cones are oval, reddish brown, and around 1.5 inches long.

Twigs: Twigs are hairy.

Bark: Young bark is finely scaled/flaky and reddish brown. Older trees have thicker irregular scales that are darker and greyer.

Appearance: Conical shape and 60-70 feet tall.

Habitat: Prefers old growth forests and rich moist sites. It is shade tolerant.

Black Spruce (Picea mariana)

Black spruce is semi-serotinous, spreading seeds after wildfires. It can also reproduce through layering, when lower branches touch the ground, grow roots, and create a new tree that’s identical to its parent.12 This helps black spruce propagate in harsh environments where seeds have difficulty thriving.

Needles: Needles are short, round, and blueish-green. They grow densely around the stem and have a small purple stain at base. There is one line of stomatal bloom on the underside.

Cones: Emerging cones are purple and ripen to grey-brown. Around 3/4 – 1.25 inches long. Cones are found at the top of the tree.

Twigs: Twigs are hairy and brown.

Bark: Young bark is reddish-brown with flaky scales that become darker with age.

Appearance: A short tree, 25-30 feet in height. Squirrels feed on young shoots at the top of the tree, which can cause a dense, club-like shape to form at the top.

Habitat: Prefers wet and acidic soils. Thrives in peat bogs.

White Spruce (Picea glauca)

White spruce is one of most common trees in the Wabanaki/Acadian forest. It’s known for its low, sweeping branches, which provide great shelter for many forest animals (deer, porcupine, birds, and rodents).4 Traditionally, indigenous peoples used its flexible roots for crafting baskets and constructing canoes.7

Needles: Needles are short, 3/8 – 3/4 inch, round, and blue-green. The underside has two lines of stomatal bloom. Some say the crushed needles smell unpleasant, like skunk or cat pee. (I actually think they smell good).

Cones: Cones are 1-2 inches long, slender, and cylindrical. Young cones are slightly purple maturing to light brown.

Twigs: Twigs are hairless.

Bark: Young bark is light grey and smooth. As bark ages, it develops scales and a deeper brown/grey colour. Scaling can reveal newly exposed bark, which is salmon-coloured.

Appearance: Pyramid shape and 50-60 feet tall.

Habitat: White spruce does well in many soil conditions, but prefers moist, well drained soils. It is salt tolerant and often found in old fields and pastures.

Other Conifers

Tamarack (Larix laricina)

Tamarack, also known as the eastern larch, stands out as the only conifer that sheds its needles in the fall. Before dropping, the needles turn a stunning golden-yellow in autumn. “Tamarack comes from the Algonquin word akemantak, which means ‘wood used for snowshoes.'”4

Needles: Needles turn golden-yellow before being shed for winter. They are found in bundles of 12-30 on short woody stems and are around 1 inch long. They’re soft, flexible, and bright green in spring and turn a darker blue-green in summer.

Cones: Cones are small, 1/2-3/4 inch, purple when young and mature to brown.

Bark: Bark is smooth and reddish-brown to grey. As the tree ages, it develops into rough scales.

Appearance: Narrow trunk, conical shape, 39-75 feet tall.

Habitat: Prefers wet and cool sites. It handles the acidity of bogs and is often found alongside black spruce and cedar.

Eastern White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

Cedar is rot resistant, making it a popular choice for shingles and garden planters. In the sixteenth-century, French explorers referred to the cedar as ‘arborvitae,’ meaning ‘tree of life,’ because they believed it protected their ship crew from scurvy.4

Red squirrels and Swainson’s thrushes use strips of the outer bark for their nests.9

Leaves: Leaves are scaly, flat, and fan-like. They are yellow-green and grow opposite in rows.

Cones: Cones are small, 1/8 – 1/4 inch, slender, bell shaped, and develop in clusters. They emerge green and mature to brown.

Twigs: Twigs are flat and reddish-brown.

Bark: Young bark is reddish-brown maturing to grey. Outer bark peels in narrow strips that form a spiral.

Appearance: Cedar trunks are often divided into two or more secondary trunks. Cedar is 40-50 feet tall.

Habitat: Prefers swamps, limestone soils, cool and moist areas.

Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

Eastern hemlock is one of the most beautiful conifers in the Wabanaki/Acadian forest. Historically, it was spared from cutting because of its poor wood quality and the stone-like hardness of its knots, which can chip steel blades.7

Today, eastern hemlock is threatened by the invasive hemlock woolly adelgid. The insect feeds at the base of hemlock needles, disrupting the tree’s nutrient and water transport systems. This weakens and eventually kills the tree, leaving stands of tall grey trees where there used to be life. Scientists, conservationists, and volunteers are working together to treat and protect these trees.

Needles: Needles are short, 5/8 – 7/8 inches, flat, with two stomatal bloom lines running underneath. Young leaves are light green darkening with age. Needles smell lemony when crushed.

Cones: Cones are small, 5/8 – 1 inches long, and pendant shaped. They begin green and mature to brown.

Twigs: Twigs have hairs.

Bark: Young bark is reddish-brown to grey with round or irregular scales. As it matures the scales become larger and bark develops deep furrows.

Appearance: Conical shaped tree with rounded top. 60-70 feet tall. Lives for 500+ years.

Habitat: Does well in many soil types. Prefers cool moist sites, mature forests, and ravines.

Balsam Fir (Abies balsamea)

Oh, Christmas tree! Balsam fir is a popular choice for the holidays. It’s also New Brunswick’s official tree, likely chosen because it’s a staple of the province’s lumber industry.10

A new study out of Dalhousie University shows that balsam fir needles are toxic to blacklegged ticks, and could be used to reduce the spread of Lyme disease. Researchers suggest that balsam fir essential oil could act as a low toxicity product for tick management and applied in the winter months.8

I’ve written an entire post about balsam fir and its uses here.

Needles: Needles are flat, dark green, and smell like Christmas tree. They’re 3/8 -1 1/2 inches long.

Cones: Cones are 1-3 inches long, purple-green to dark brown, covered in sticky resin, and stand upright on branches.

Twigs: Twigs are smooth, red-brown, and oval.

Bark: Young bark is smooth, grey-green, and has small dash-like lenticels. Bark is often covered in resin blisters which can ooze.

Habit: Conical shape, 40-60 feet tall.

Habitat: Moist, sandy, and acidic soils.

Identifying Conifers

I hope this post helps you identify the conifers of the Wabanaki/Acadian forest! If you have any questions or would like to share your experiences with these trees, feel free to leave a comment below.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Winter Tree Survival: The Resilience of Eastern Canada’s Forests

Wabanaki/Acadian Forest: History, Species, and Biodiversity

Balsam Fir: A Guide to Identification and Uses

Maple Trees and Their Edible Qualities

Identifying Conifers Sources

1 Julian Gwyn. “The Halifax Naval Yard and Mast Contractors, 1775-1815.”

2 Kelley Arnold. “A Youth’s Guide to the Acadian Forest.”

3 Lynn Rogers. “The Black and White of It: Black Bears and Their White Pines.” bearstudy.org.

4 David Palmer and Tracy Glynn. 2019. The Great Trees of New Brunswick 2nd Edition. Goose Lane Publishing.

5 Government of Canada. “Nova Scotia’s Provincial Symbols.”

6 Katie Hartai. 2017. “Local Biologist Says Fewer Softwood Trees in Nova Scotia Means Intense Challenges for Forest Life.” CityNews.

7 George A. Petrides. 1988. Eastern Trees. Peterson Field Guides.

8 Alison Auld. 2022. “Balsam Fir Needles Could Help Kill Blacklegged Ticks and Reduce the Spread of Lyme Disease, Study Shows.” Dalhousie University News.

9 Michael Wojtech. 2011. Bark: A Field Guide to Trees of the Northeast. Brandeis University Press.

10 Government of Canada. “New Brunswick’s Provincial Symbols.”

11 Ken Denniston. 2015. “Stomatal Bloom.” Northwest Conifer Connections.

12 Nature Conservancy Canada. “Black Spruce.“

Conifer ID Info:

Michael Wojtech. 2011. Bark: A Field Guide to Trees of the Northeast. Brandeis University Press.

George A. Petrides. 1988. Eastern Trees. Peterson Field Guides.

Jeffrey C. Domm. 2021. East Coast Trees & Shrubs. Formac Publishing Company.

David Palmer and Tracy Glynn. 2019. The Great Trees of New Brunswick 2nd Edition. Goose Lane Publishing.